Lynne Viola, a University Professor with the Faculty of Arts & Science’s Department of History, has been honoured with the Gold Medal from the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council (SSHRC).

Viola is a leading scholar of Soviet history and recognized around the world for her archival research into the Stalinist era, focusing on the Soviet dictator’s mass repression of its people in the 1930s.

“I was very surprised and humbled,” says Viola of winning SSHRC’s highest research honour among its annual Impact Awards.

With this most recent achievement, Viola has accomplished something few have done — she has completed a rare ‘hat trick’ in Canada’s highest academic honours.

“This is a remarkable accomplishment,” says Melanie Woodin, dean of the Faculty of Arts & Science. “Lynne is only the fifth scholar to win the Molson Prize, the Killam Prize, and now the SSHRC Gold Medal — our three top national humanities and social sciences awards. These honours are a tribute to her passion and fearlessness in sharing knowledge about Stalinist Russia that continues to benefit students and scholars at U of T, as well as around the world.”

How does Viola feel about blazing a trail of academic achievement?

“It brings on a strong case of imposter syndrome,” she says. “With all the recognition, it's a bit overwhelming.”

put his own secret police on trial for crimes

he sanctioned.

Voila first joined U of T in 1988, delving into her research and teaching with academic awards being the last thing on her mind.

“If I had been thinking in those terms, I never would have gone into academia,” she says. “My motivation was always to just have a better understanding of 20th century Russian history.”

For more than 20 years, she’s shared that understanding with thousands of students, with a strong emphasis on training graduate students.

“The best part of teaching PhD students is seeing them launch — going off to do research in Russia, Ukraine and elsewhere, and seeing them land jobs and produce books,” says Viola who has trained more than 20 successful PhD candidates.

Viola has written five books, and though pleased with all of them, she is especially proud of The Unknown Gulag: The Lost World of Stalin’s Special Settlements, published in 2007.

The book chronicles how Stalin drove two million peasants into internal exile to work as forced labourers in the early 1930s. Families were thrown out of their homes, banished from their villages and sent to remote icy regions where over a decade, almost a half million died from starvation or disease.

Providing a new dimension of Stalin's brutality, The Unknown Gulag stands alone as the first book in English to explore this story.

“I was able to follow the peasants to their places of exile, so I told the story through their voice and presented a framework for understanding the insane planning that went into the whole endeavour,” she says.

For much of Viola’s work, access to archives is paramount. Over her career, she’s made more than 25 trips to Russia and seven trips to Ukraine in search of archives and answers to Russia’s sometimes violent and turbulent history.

Photo: Lynne Viola.

Access to such archives often depends on Russia’s or Ukraine’s political climate, which often adds a level of complexity to her studies. “That's what makes it interesting,” she says. “It’s sometimes frustrating, but never dull.

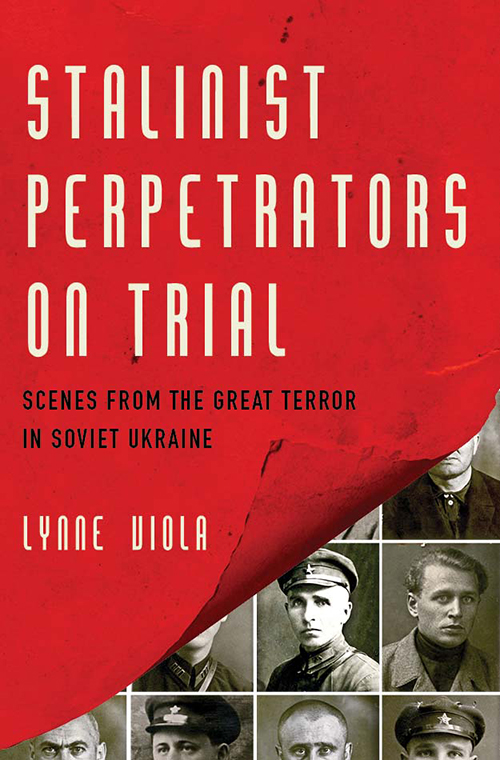

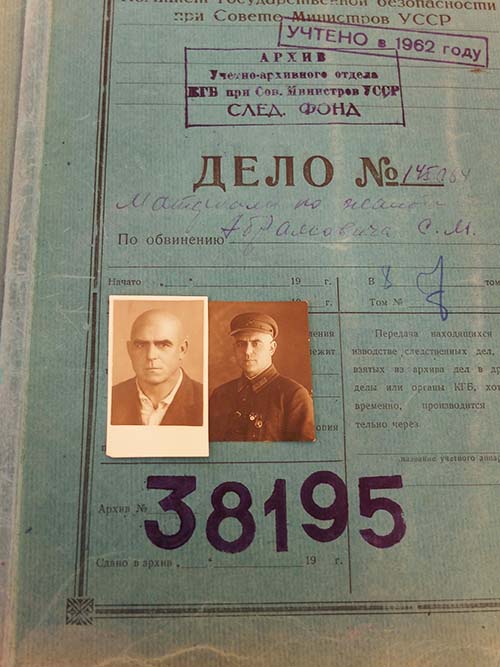

“My most recent book is based on fairly newly opened archives in Kyiv, archives of the former KGB,” says Viola, referring to her 2017 book, Stalinist Perpetrators on Trial: Scenes from the Great Terror in Soviet Ukraine.

She referenced previously classified documents to outline Stalin’s purge of the Soviet secret police in the 1930s. Filled with grim stories of torture and executions, Viola captures Stalin’s chilling story of how Stalin turned the tables on members of his secret police and put them on trial for crimes he personally sanctioned.

“The materials for this book were completely new, nobody had worked on this before,” she says. “They were some of the most extraordinary documents I've worked on in my career.”

Despite all the trips, research and books, the hunt for more archives continues. In fact, the SSHRC Gold Medal prize of $100,000 will certainly be used to fund future trips overseas, says Viola.

She hopes to uncover and publish more archival documents, not only for her own research but for scholars across the globe as well as the general public, preserving Russia’s history, especially in light of the return of an authoritarian government.

“That’s the other side of my work,” she says. “On the one hand, I'm publishing my own books, but I've also led several international collaborative research teams since the 1990s, and most recently in Kyiv, publishing collections on various topics. I’ve learned so much by working with these international collaborators who have local knowledge.”

Was she ever nervous about going to Russia or Ukraine and searching for files that governments might not want to be found?

“I was never nervous about the political situation,” she says. “In earlier periods like the 1960s, they sometimes did bother academics. In Soviet times, pre-1991, there were bigger fish to fry like diplomats, journalists, and people in business, so by that time they generally left academics alone.”

Having been on sabbatical for the past year, Viola is looking forward to being in front of students again in January. However, she did find teaching international online seminars and workshops during the pandemic also had its benefits.

“I loved it,” she says. “I had one student in Shanghai who would be up in the middle of the night to take my class. I just loved having students from all over the world pop in.”